She walks up to me and extends a greeting, but all I see are her eyes and I miss the first attempt at shaking her hand. Those captivating and mesmerizing eyes she has; they will haunt me forever.

She is a camel milk producer, living in the small remote town of Bambas in Ethiopia near Jijiga, in close proximity to the Somalian border. Her days are spent milking camels at the break of dawn, collecting the milk in antique wooden containers, the interiors burned by fire to instill a nice smoky taste to the milk. (Hear Fatumo milking her camels)

She pours the milk into larger containers and then carries the heavy load miles away to either sell the milk by road side, or give it to milk collectors who will then take the milk to market. Her work is assisted by programs developed by Mercy Corps.

And the next day is the same as today.

She tends to her children, she collects firewood in the distant fields, she prepares dinner for her family, she feeds the animals and cleans their spaces, she settles neighborhood disputes, she sweeps the hay from the floor of her hut. And she looks for water, desperately at times, a scarce resource in this drought-prone area of Ethiopia.

And the next day is the same as today.

She has a quiet yet bold demeanor and when she looks at me, she looks into me. Her eyes never leave mine, and with her chin slightly tucked in and eyes constantly seeking mine, I cannot help but think that she knows how the power and grace she exudes has an effect on others. I muster up something, anything, to break the spell she has on me, but it doesn’t work. I ask her how old she is, and her answer is I am woman.

She looks at my travel clothes and makes her first observation toward me: You will never attract anyone dressed like this. Try adding more color to your style.

And on it goes, one observation after the other, her to me, and me to her. I want to touch her face, but then I realize it is only because I don’t really believe that she exists. She must be a dream. As if she knows what I am thinking, she extends her hand and touches mine, eyes never wavering her intentions.

I cry.

I feel my belly turn upside down and I know this is so inappropriate. Crying in front of an Ethiopian beckons all kinds of feelings and it is highly disturbing to them. I swallow it all, turning away to say something, anything, about the beauty of her home.

We spend the day together, and she shows me what she does all day long, every day. We visit the other milk producers and initiate song and dance among them, pounding beats on the makeshift plastic milk containers as our drums, me singing the Somalian words that I did not know that I knew. (Hear the milk producers singing)

I return the next day before the sun rises, and she shows me how to milk a camel and what camel milk tastes like right after it has been collected. We walk in silence over sandy fields strewn with beautiful pink sparkly rocks and I try to reason with my soul why I should return home. I want nothing more than to stay longer, learn from her, feel my body adjust to constant movement to obtain nourishment. She knows what I am thinking, and she asks me to stay, inviting me to live in her village with her. I can’t even answer her right away, walking in a stupor as I wonder how she truly is able to read my mind.

I dream of living a life of simplicity, making my own music and dancing when I feel like it, listening to birds awaken me each day and wearing colorful scarves and dresses and greeting visitors in the manner in which she does. And I know I will never be like her.

I know I will return home and acclimate back into my own culture and sit at my computer and write about her, longing for this kind of exchange, deep exchange, with people back home.

And I know that our manufactured distractions will prevent me from doing this, and I might feel happy but deep inside, if I am honest, I often desire a deeper human connection in my every day. Or I won’t long for this, and instead I will replace my longing with pleasure garnered from material goods and the next travel destination and a plate filled with some chef’s concoction.

I turn to her to say goodbye and this time I can’t hold back the tears. She gasps, and waves her hand back and forth in front of me.

No, no, NO! Don’t cry. Saying goodbye is part of life. Are you not a strong woman?

And with that, she turns and walks away.

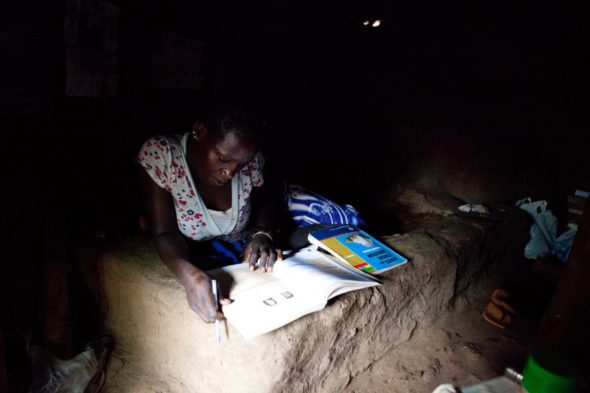

(All images for Mercy Corps)