Earlier this year while I was on assignment for an NGO based in Mekele, Ethiopia, I had the unique opportunity of visiting the incredible landscape of the

Danakil Depression along with my colleague,

Dardinelle Troen, and two employees of Mekele University.

For us, it was an epiphany to stumble upon this unbelievable and yet relatively undiscovered corner of the world. Everything was unexpected: the place, it’s unique geology and landscape, the people and their unique way of life. One highlight was our encounter with a mile-long camel caravan led by salt miners on their way to harvest salt from the vast salt pan we found ourselves driving across. I imagined these men traversing the same well-worn paths traveled historically for countless centuries dating back to the pharaohs.

While visiting this area, and as an excuse for making a personal connection, we stopped to take a few instant print photos of the men as they passed by, gifting them the print in exchange for a moment of interaction. Their excitement and appreciation reinforced enthusiasm for one of my personal projects, Prints For Prints.

In 2013, I founded Prints For Prints, a volunteer organization which brings photographers and equipment to remote corners of the world to set up portable photo studios. A family photograph is a precious thing to many of us, and especially so to people who live in remote areas. Often in areas so far away, many do not have a record of their children, their elders or even themselves. We feel strongly that a photographic print is a wonderful way for loved ones to remember each other, whether they have passed from this life or are thousands of miles away carrying salt to Somalia. Our purpose is to create a physical keepsake that documents and preserves a moment in time to be shared, remembered and passed to future generations.

As we’ve learned time and again in our journeys, contained within the portrait process is an opportunity to make a personal connection. In the course of capturing a picture, we shared an intimate moment exchanging glimpses into each other’s hearts and inner psyches. Warmth, humor, vulnerability, and sorrow all expressed in an instant.

This aspect was reinforced again during our brief time in the Danakil. It was a bit intimidating when we approached the salt miners in their caravan; they seemed rather intense and brooding. Even after overcoming the language barrier and agreeing to have their pictures taken, they still each gave a purposeful grimace when they stood for their portraits. It only struck us after a few moments that it was partly swagger as we watched each person being cajoled by his traveling mate as they each shared their small mementos with each other. This gesture opened the gates of wishes, and we were asked by many others to make more prints.

In every venture of Prints For Prints, we consistently find ourselves drawing a crowd. Many times we find ourselves surrounded by burgeoning local photographers seeking to advance their skills. We make the most of these opportunities by making space in our process providing educational mentoring, either one-on-one with individuals or through partnerships with local schools, and we include students in our field photographs. We hope this opportunity to pass on our photographic expertise to a local community will sow the seeds for a developing photographic industry, as the passion for the craft is very apparent.

While experiencing this remote region and its natural beauty and seeing the salt miners’ joy upon receiving their instant print, we realized that there is a larger potential for storytelling here. Up until now, Prints For Prints’ primary focus has been connecting photographers to their subjects and leaving behind high-quality prints and the intellectual tools and inspiration for a continued photographic industry.

But there is more substantial potential as a vehicle for authentic exploration and storytelling of the area and bringing these stories to a larger audience. In a world struggling with a rise in polarization and nationalism, there is a need for a greater inclusiveness that celebrates our diversity and perhaps redefines our preconceptions of “others.” Making an intimate human connection in the same way a photographer connects to their subject in the process of making a portrait is a way to cross cultural divides.

We envision the Prints For Prints expedition as a vehicle for an authentic exploration of a locale by getting to know its people on a more intimate level while finding and documenting the anecdotes and rich stories that inform their life experiences along with those “1000 words” imbued in their portrait. Creating cohesive documentation in beautiful images, stories, and video can then be re-purposed in a variety of platforms: print, publications and social media to bring awareness, tourism, and commerce to the area.

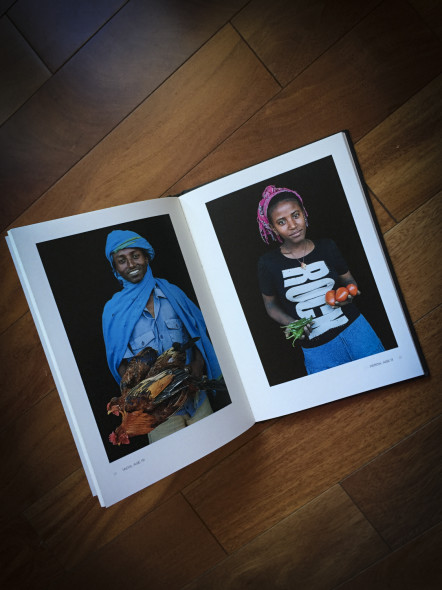

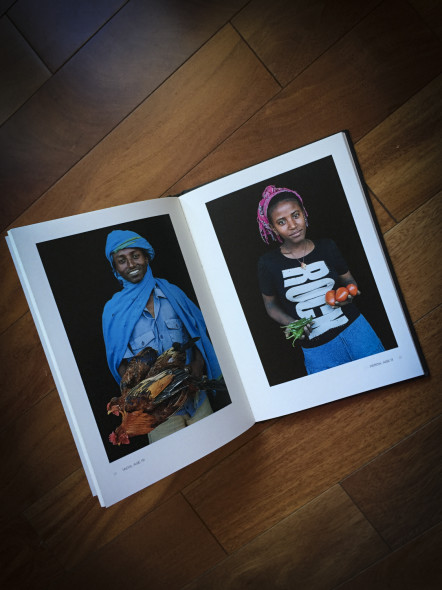

Photographing each subject against a portable backdrop, we intend to create portraits as they hold artifacts they bring with them on their nomadic journey.

We are seeking support via project sponsorship or monetary coverage/discounts of expenses. In exchange, we will be promoting the experience and story, in traditional publications and social media platforms. The resulting photographic assets, videos and written stories will be available for sponsors to use for their marketing and promotions, as applicable.

Through our work with organizations such as Travel Oregon, we have repeatedly seen how this process results in success in reaching a targeted, diverse audience. Travel Oregon depends heavily on image based promotions to draw in tourism from around the state and region each year.

For further information about our experiences with Prints For Prints, please visit our website at www.printsforprints.com. We welcome any questions regarding our process, past experiences and budgets for upcoming project work.

Should funding or service donations be secured, our next proposed trip will be to return to the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia in February of 2018 to give those salt workers the photo prints they asked for, as well as some much desired sunglasses that have been collected by people living in a small assisted living home in Coos Bay, Oregon.

(Seaside Stichers, photo by Mary Luther, Activities Coordinator)

If you would like to donate in-kind goods, airline miles, accommodations, transportation, translation services or financial support, please contact us by sending us an email or donating directly on our Prints For Prints donation page.

We appreciate any level of support!

You can see more images from this location in the Afar region of Ethiopia in my stock image database here. This project will also extend my earlier Market Workers project, celebrating those behind the developing world culinary scenes who bring spice and other delectable tastes into our lives.

Thank you for considering any level of involvement and support!