The women file into the room, their colorful dresses accentuating their inherent cheerful spirits. They are all fistula survivors, and they are here to help spread joy and encouragement to those who are still suffering from this condition. They have been here before, and they know the isolating despair they felt when they were leaking urine and feces down their own legs.

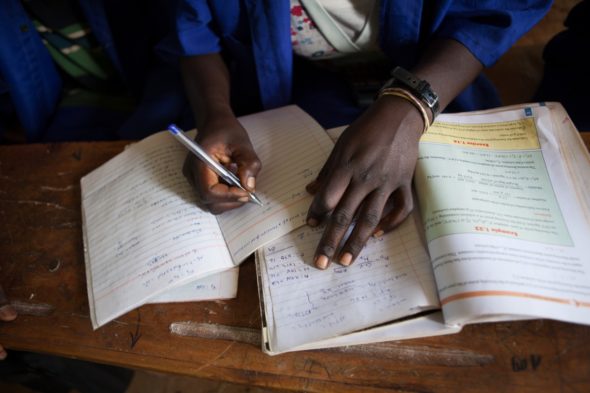

But today is a new day. They have been healed by the hand of a skillful surgeon and they are now participating in reintegration skill training at Terrewode, their programming funded by the Worldwide Fistula Fund, in the beautiful Soroti region of Uganda. Sewing, jewelry and basket making, bread baking: the products of all of these activities can be sold in markets and and is a way for these women to get back on their feet and feel productive once again. They are here to learn these skills, and also participate in a performance for us.

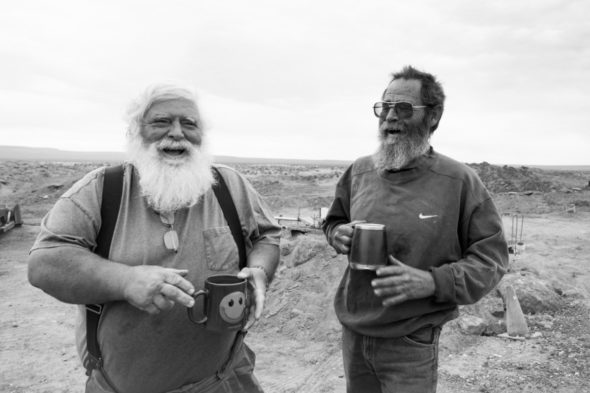

The African man suffers a generalized stigma that portrays him as typically uncaring, a tyrant who dominates women, marries them at an early age, and abandons them when when they become ill. While these things do happen across our globe, there is another side to this portrayal; concern for women by males in African countries also can be seen readily if one spends any time in villages.

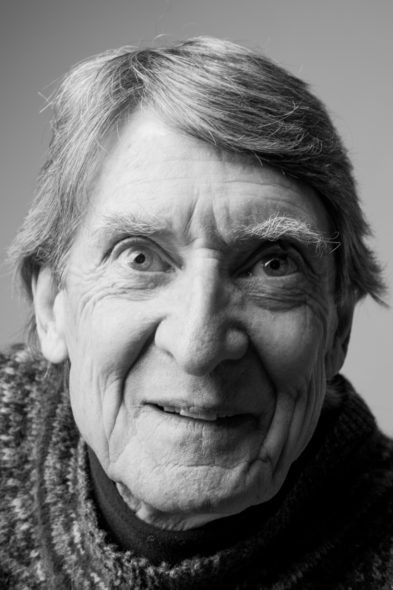

Stephen Otim uses music to attract others to the joyful sounds heard in the distance. In various villages, people gather to see the colorfully clothed dancers and to watch the drama unfold before them. The message in the lyrics and in the dialog all centers around educating others to look for signs of obstructed labor and also to refer a loved one for care should she develop a fistula. Through music and drama, this group is removing the shameful stigma associated with fistula, and in its place they are helping men and women rally around the condition.

One by one, more men ask to become a part of the festive ensemble. They not only understand the issues surrounding maternal care, they feel a sense of responsibility and a surge of motivation to spread maternal health education further. Young men, old retired men, boys: they all want to be a part of this collective concern for their wives, sisters, mothers and daughters.

Each day, approximately 16,000 women die or suffer serious complications from causes related to pregnancy or childbirth. Every six seconds a mother-to-be experiences a life-threatening complication.

I think we all have some work to do.

Music heals, beckons and is a universal language that has no boundaries. Stephen picks up his thumb drum, smiles at my young Moroccan male assistant who has been busy setting up equipment, and says slyly “Would you like to learn how to play?”

(Update: I will be returning to Uganda in November 2015 to work on documenting the music and dance troop’s performances and to assist with an Oregon-Uganda goat milk soap making project. Donations for this work are greatly appreciated. Send us an email if you would like to hear more about these two projects. You can make a donation here. Specify “Soap Project” or “Music Project”)

View a video of the musicians and dancers in their village here.