(Photo by Sean Sheridan for Mercy Corps)

Category Archives: Essays

Guest Post: Kerry Reinking

Photographer Kerry Reinking traveled from Amsterdam and experienced a whole lot more than he expected while traveling to Addis Ababa and Bahir Dar.

(Image of the back scenes of photographing The Market Workers series by Kerry Reinking)

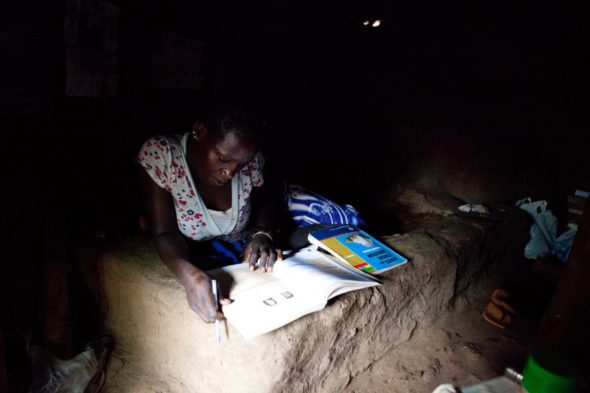

Coconut Oil + Education

Kuye is one of very few girls who get to attend high school in this southern area of Ethiopia. This is not due to a lack of desire, they simply have too many duties to perform at home and the costs to attend school are outside of most families’ reach. Within Kuye’s class, there are 42 students and only four of them are girls. (Hear students at Konso High School)

Kuye’s mother, Taiko, notices other girls at the market who are educated and wants the same for her daughter.

Taiko was able to obtain a scholarship and academic support via a program developed by Mercy Corps. Kuye is flying down the path toward her education goals. Her favorite subject is social science, which includes computer programming, and she wants to become an engineer. She has seen women in other countries work in this field, and she believes it is time for Ethiopia to have more female engineers.

Kuye knows that she is a pioneer of sorts. There are people in her village who still think a girl “is not a good girl if she goes outside of her house” to do things outside of her traditional activities. To some, this might seem patriarchal and dismissive of women. But it is more complex than this simple conclusion. Girls are highly regarded in Ethiopia and they are cherished to the point of believing they will (and knowing they can) be stolen, and therefore they are highly protected.

Most women who are not educated end up living a life full of extreme physical burden. They fetch water and firewood, carrying bundles of heavy loads for miles, sometimes days, to help provide for their family. They suffer during child birth, often losing their baby and living with resulting injuries obtained during days of laboring. Life indeed can be hard in the rural areas of Ethiopia, for both men and women.

Kuye wants to alter this path, and show the world how capable a woman in Ethiopia can be. I give her my camera, and she quickly learns how to operate it, snapping a photo of her mama Taiko and gleefully turning to all of us with excitement about the beautiful image she just captured.

She is a quick study, smart as a tack.

Her hope for her future is to “finish school, get a good test result and go to university, then return” to help her village. I can only imagine what she would do if she attains this goal.

She cites gender inequality as being an issue in Ethiopia, but she has a simple reason for its existence. She points to the fact that boys, at an early age, begin to carry heavier loads than she can carry. They appear stronger and and more powerful, just because they can pick up heavier objects. Kuye believes that gender equality begins at home, with each parent treating boys and girls equally, and instilling within a young boy’s mind that his sister is as strong as he is.

I ask her where she studies when she is home, and she shows me her bed made of mud and clay. To the left of the bed is a small shelf made from hay and mud and I notice again the coconut oil. This is a prized possession, as it makes her feel beautiful and a part of the group of students in her class. Like any 18 year old student, she wants to fit in.

And she wants to feel like a girl, all pretty and smelling wonderful as she faces her new world and emerges as a strong and educated woman.

I will cheer her on. all the way through her university years.

One coconut oil jar at a time.

(Photo of Taiko above by Kuye Orkaydo)

(All images for Mercy Corps)

Something, Anything

She is a camel milk producer, living in the small remote town of Bambas in Ethiopia near Jijiga, in close proximity to the Somalian border. Her days are spent milking camels at the break of dawn, collecting the milk in antique wooden containers, the interiors burned by fire to instill a nice smoky taste to the milk. (Hear Fatumo milking her camels)

She pours the milk into larger containers and then carries the heavy load miles away to either sell the milk by road side, or give it to milk collectors who will then take the milk to market. Her work is assisted by programs developed by Mercy Corps.

And the next day is the same as today.

She tends to her children, she collects firewood in the distant fields, she prepares dinner for her family, she feeds the animals and cleans their spaces, she settles neighborhood disputes, she sweeps the hay from the floor of her hut. And she looks for water, desperately at times, a scarce resource in this drought-prone area of Ethiopia.

And the next day is the same as today.

She has a quiet yet bold demeanor and when she looks at me, she looks into me. Her eyes never leave mine, and with her chin slightly tucked in and eyes constantly seeking mine, I cannot help but think that she knows how the power and grace she exudes has an effect on others. I muster up something, anything, to break the spell she has on me, but it doesn’t work. I ask her how old she is, and her answer is I am woman.

She looks at my travel clothes and makes her first observation toward me: You will never attract anyone dressed like this. Try adding more color to your style.

And on it goes, one observation after the other, her to me, and me to her. I want to touch her face, but then I realize it is only because I don’t really believe that she exists. She must be a dream. As if she knows what I am thinking, she extends her hand and touches mine, eyes never wavering her intentions.

I cry.

I feel my belly turn upside down and I know this is so inappropriate. Crying in front of an Ethiopian beckons all kinds of feelings and it is highly disturbing to them. I swallow it all, turning away to say something, anything, about the beauty of her home.

We spend the day together, and she shows me what she does all day long, every day. We visit the other milk producers and initiate song and dance among them, pounding beats on the makeshift plastic milk containers as our drums, me singing the Somalian words that I did not know that I knew. (Hear the milk producers singing)

I return the next day before the sun rises, and she shows me how to milk a camel and what camel milk tastes like right after it has been collected. We walk in silence over sandy fields strewn with beautiful pink sparkly rocks and I try to reason with my soul why I should return home. I want nothing more than to stay longer, learn from her, feel my body adjust to constant movement to obtain nourishment. She knows what I am thinking, and she asks me to stay, inviting me to live in her village with her. I can’t even answer her right away, walking in a stupor as I wonder how she truly is able to read my mind.

I dream of living a life of simplicity, making my own music and dancing when I feel like it, listening to birds awaken me each day and wearing colorful scarves and dresses and greeting visitors in the manner in which she does. And I know I will never be like her.

I know I will return home and acclimate back into my own culture and sit at my computer and write about her, longing for this kind of exchange, deep exchange, with people back home.

And I know that our manufactured distractions will prevent me from doing this, and I might feel happy but deep inside, if I am honest, I often desire a deeper human connection in my every day. Or I won’t long for this, and instead I will replace my longing with pleasure garnered from material goods and the next travel destination and a plate filled with some chef’s concoction.

I turn to her to say goodbye and this time I can’t hold back the tears. She gasps, and waves her hand back and forth in front of me.

No, no, NO! Don’t cry. Saying goodbye is part of life. Are you not a strong woman?

And with that, she turns and walks away.

(All images for Mercy Corps)

The Fear Of Affection

Rhythm and swoon, their bodies meld, back and forth they sway, eyes locked on each other, hands waist level with fingers rippling like a sea of fish in an ocean of love.

Two men, friends, in Ethiopia.

In Western culture, we would label this display of affection as something other than a respectful acquaintance. But here in this land where mankind first existed, love is shared between men in a highly sensual, if not downright, erotic manner.

This, in the light of day, outside, in fresh open air.

For God’s sake.

The first time I saw this type of electricity pass between hard bodied and uber masculine men was in a dark bar, tucked away in the Piazza area of Addis Ababa. I watched in amazement as men beckoned one another to dance, their bodies aligned with the thump of bass that was spilling out of the too-close speakers. As two men conversed with dance, they each started out with patterned steps, tentative with each move, but always maintaining eye contact with each other, lest one might break the spell.

As they warmed up, in body and spirit, their movement became more erratic, but with more fever to stay on beat, and aligned with each other, legs woven. They are that close.

Do they have sex?! I blurt out, my USA need to label rising to my speech.

No. No, they don’t. They are friends.

Then how can they look at each other like that? Like THAT.

Once again, as often happens here, my words solicit a reaction of tilted-head amusement at my questions.

But, of course. Why wouldn’t men love one another? And show it? Isn’t this how we were born to relate?

I continue to watch with humble heart, feeling silly for asking such questions. Then, out of the corner of my eye, I see my Ethiopian friends watching me, intently, as I watch the swirl of energy in every direction.

You silly Western girl. Why does this fascinate you so?

I feel rhythm beckon me, and with tempered manner and the thrill of a new encounter, I take the hand of my friend.

The Pendleton Round-Up (aka The Pendleton Pound ‘Em Down)

Miss Terri, owner of “Terri’s Dirty Blonde Salon”, is in the house.

I first met her last year at the Canby Rodeo while I was photographing rodeo riders with my Speed Graphic 4X5 film camera. As I fumbled with the low light conditions, I reached for my dark cloth, and instead almost plunged my hand into her ample and adorned-with-a-huge-shiny-necklace cleavage.

Hi, I’m Terri!

She proceeded to rattle off cowboy names and stats, peppering the conversation with a bit of rumor here and there just to make sure I was listening. Her passion for the rodeo was unlike any sideline sports fan I had ever met. And yes, it extended past the “I want a sexy cowboy” quest.

We met several other times at other rodeos (imagine her glee when I got us press passes for the dressing room at the Mollala Bull Riding Competition) and throughout the year she kept me informed via text messages about champion rides, marriages and divorces, broken legs and even the death of one of her favorite riders who was her dear friend.

Her heart is big and unbound. She brings her scissors to each rodeo and cuts the riders’ hair when they need it, feeds them chips and salsa, gives them a soft place to pass out in her trailer after a night of too much whiskey. She’s a good girl.

And a sexy mother hen to boot! At home, she cares for her beautiful thirteen year old daughter and her erratic and loving autistic son. Sparkly and girly and bold and strong as a man, she drives a monster truck and hitches her trailer by herself, thank you very much. And she can shoot a gun like a bandit.

This week we are at the Pendleton Round-Up, the Mother Lode of Rodeos. After finishing our plate of bad Mexican food, we head over to her usual evening starting point, The Hut. We meet up with her cowboys and they take turns feeling her breasts, betting whether they are real or not. They have to check a few times to make sure their previous conclusion was correct. Oh, Terri.

Before I finish my Pendleton Whiskey on the rocks, she grabs my arm and swings me toward the door. Time to go downtown. I pony up to walk a mile in my cowboy boots, when I see a bull rider run into the street and stop a flat bed truck. On we pile, and away we go. This is how the cowboys get their rides downtown! (A few days later I try this technique on my own, and it doesn’t work. I had to resort to hitting up people in trucks waiting in line at the Taco Bell where they were trapped and had to listen to my sorry begging for a ride.)

We make it downtown, and one exceptionally sturdy cowboy who had seen my attempt trying to jump up on the flat bed fail miserably lifts me onto his shoulder like he would a heifer, and in a jiffy I am on solid ground again.

We make our way straight to Crabby’s where Terri tinkerbells her way around the room. Boy, Man, Girl, Woman….everyone watches Terri as she sashays her way to the bar to the dance floor and back to the bar.

I learn to dance the Cowboy Swing, taking home arm bruises to prove that I lost my battle to try to lead these bull riders.

And I vow one thing before the night is over: tomorrow I will bring my stick horsie with me and get these rowdy boys to ride THAT.

I think Terri would approve.

(This account was written about Day 1 of the workshop I taught at the Pendleton Round-Up. I was sworn to secrecy about Day 2, 3 & 4.)

(Last photo courtesy of Terri Nicol)

Father’s Day Musings

Some of the celebrants will be mothers, deliberating how they can best celebrate this day, when no papa is in sight. Some will be old men, their children long moved away focusing on children of their own. Some will be “kinda dads”, as my daughter calls step-dads.

This is a tribute to all Fathers out there. Those who love well. Those who try their best. Those who feel shame because they can’t pay child support. And yes, even to deadbeat dads, because deep down, we all know you love those children you fathered, even in your cowardly ways. I occasionally see you, sitting at some event, eyes flickering more rapidly, your body braced slightly backward toward the exit as you look at someone’s family photos that have been brought out before you.

I have had my share of relationship difficulties along the way, with some situations brought about by my own hand. I too have regrets regarding my own behaviors, especially toward the father of my three children. We still remain strongly bonded, together, for our kiddos, continuously seeking better ways to parent them, looking for ideas regarding how to support all three of them now that they are in college, and wondering if the worry will ever end. I love this man like no other, and have learned so much from him, still do, even though we parted as marriage partners many years ago. I still photograph him, in the same t-shirt, flipping pancakes every Christmas morning. Haven’t missed a December 25 morning in twenty-five years. Some of my new relationships could not accept this. Those faded away.

Last month, I encountered a young boy crossing the park as I was photographing subjects in my outdoor studio during a street photography event. I saw his downtrodden face, and normally I never seek out someone to photograph who appears down and out, but something drew me to him, and since I’ve long ago learned to act on my instincts, I started talking with him.

He told me that he was homeless, has had significant troubles in his twenty-something years of his life, and was just, well, he was just wandering. No where to go, really.

He then told me about his quest to see his son again one day. It has been many years since he last saw him. He pulled out a battered and frayed photo of a child that looked to be around six months old.

“He’s about four years now. Bet he’s walkin’ and talkin’ by now. Maybe one day she will let me see him again,” he said through a mouth full of broken teeth.

I gave him my card and offered a free photo session in my studio if he ever does get to see his child. I doubt I will get that call.

This boy still haunts me.

I started writing these musings because today is the start of a little miracle journey. Three years ago, as I sat on my couch with my boyfriend from high school days and his then girlfriend, we looked at the images I recently brought home from Ethiopia. Many faces peered up at us, each one with a more loving look than the other, with a depth of eye contact we rarely see here in the USA. Cecil and Sonya looked at each other and asked the question, “Should we adopt a child one day?”.

That was then, and today is now, as they board a plane to Ethiopia this morning, as husband and wife, to go meet their new nine-year-old son. They will meet each other for the first time this weekend, on Father’s Day. This story is a miracle because Cecil was instrumental in his teenage days in pulling me out of the depths of an insanely abusive household to stay with his family on their farm twenty miles away so I could find my way to a happier life. And ultimately to secure a family role model that I count on to this day as I parent my children.

Ah, the cycles of this life!

Cecil’s father, who I considered to be my own fatherly role model since my father could not perform his, died last Fall, a mere few months after his wife of over 50 years passed away.

Ahh, the cycles of this life.

We are human. We make mistakes, as parents, friends, siblings, co-workers and in every attempted role. I like to think we try to do our very best, each day. And maybe that is just enough. I have a theory that, upon knowing we are at our last breath, we all will hastily look back and say “WAIT! My life wasn’t so bad! I want one more minute of it!”

This Father’s Day, I will think about this little Ethiopian boy who has waited for nine years to be united with his family. I will celebrate my ex-boyfriend and my ex-husband as they live their new lives with their lovely new families.

I will think about my father, who never started out thinking he would create a lot of harm in his path, but he did, and he is still my papa.

I will give thanks to Cecil’s father, who steered me well with words such as “As soon as you learn to make strawberry jam, Joni, move on to something else. Don’t rest your laurels on past accomplishments. Just stay steady and curious.” I imagine he had a hand in steering his son from afar to adopt a child from the place I finally feel is my true home.

I will revere all of those fathers who struggle hard to put food and water in front of their children each day, all over the world.

I will think of my good friend Daniy in Ethiopia, who at twenty-three years old is capable of being a father to his father.

I will think about the fathers who never had a child, but always wanted one.

And I will wonder about my sons. What kind of fathers will they be, biological or pseudo?

Happy Fathers Day, to all fathers of all flavors and kinds. I bet you are loved far more than you realize.

Ahh, the cycles of this life.

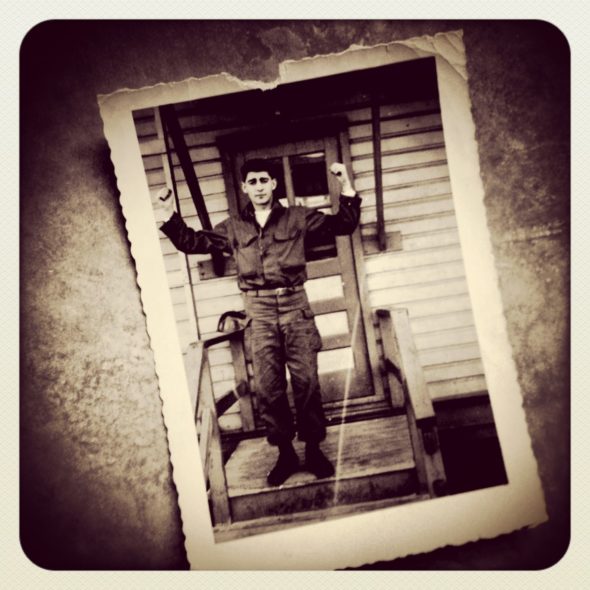

Cecil and I, photo taken by Cecil while we were in high school

My two sons, Aaron and Ben, with their papa, Marty in jammies I bought for them

Marty, flipping pancakes, December 2011

A Malagasy father, caring for his chlidren

An Ethiopian boy, around the same age as Cecil’s new son

An artifact representing a young father’s quest to see his son again

My papa, during the Korean War, before alcohol took him down

Sonia, Addisu & Cecil in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (November 2012)

Hello Al Pacino

All I hear is a mumbled “Al Pacino”.

What?

“Al Pacino is coming here. I’m waiting for him. I’m gonna wait four days for him. Right here.”

My gut tells me to walk by, eyes ahead, avoiding the possibility of incidental contact. But that’s not why I am in the Castro District of San Francisco today. I am here to take photographs. I stop to look into his pleading and exceptionally beautiful green eyes.

“When is he coming?” I ask.

He doesn’t hear my question. Instead, we start to list all the movies we could think of that Al Pacino is in. And then, as though he finally registers my initial question, he nods upward toward a poster on the Castro Theater wall announcing that Al Pacino will be there in a few days for a movie opening.

My inner Midwestern upbringing good-girl mentality kicks in, and my brain goes straight to: “Don’t photograph this poor soul. It would be exploitative.” But my gut is starting to have the upper hand in my life these days, and I proceed to hang up my piece of black velvet with the help of my body-builder friend Mark who had agreed to meet me there. I can’t get it to stick on the side of the building because of the soppy rain spots, but Mark helps to hold it in place. When I bring my camera out, Mr. Castro perks up, as much as his wobbling head will allow.

“Want me to photograph you?” He chokes out the words, a little shy-boy look across his face peering out from behind his dangling wet hair.

Sure! (Are you kidding me?)

I give him my camera making sure to secure the strap to my hand. He’s an active, erratic and currently high addict. His eyes get glassy and he tries to take the camera from me, saying he needs to get a better handle on it as he frames me. I don’t let go.

He can’t find the shutter release, even though I show him about ten times where it is. His fingers keep slipping off the camera. He starts to fall. Twice. My hand grips the strap even harder, waiting for him to begin his descent, ready to whip the camera over in my direction before it could crash along with him into the sidewalk.

What in the hell have I done?

When he finally snaps the photo, I try to pry the camera from him, but he insists that he needs to hold it to see the photo. I say ok, no problem, and try to show him how to view it on the back of the camera. He reluctantly lets go, but not without first looking stoically into my eyes and holding his gaze on me, as though to say, I know your game. You would never trust me.

I start to pack up, giving up the notion to photograph him, as badly as I would like to do it. He is right: I don’t trust him. He does scare the hell out of me. I have no business being there, in his world, as I, dressed in new Diesel jeans with a healthy check on my own vices, am tipping on the edge of my security, and he, not in the same stage as I in his life, could live as free from structure as I could only imagine.

As I put my camera in my bag, I heard Mark murmur under his breath let’s get the hell out of here.

“Don’t you want to photograph me?”

The sound of his strained voice jolts me.

He asks a second time. I get my camera back out, this time searching his face and locking my eyes into his.

As I look at these images now at home, he haunts me. We all start out as little precious beings, seeking love and attention and a safe place to rest our heads and our hearts. I study his worn yet lovely face. Cleaned up and sitting at a desk in some corporate setting or spinning records in a downtown hip venue, he would be a strikingly handsome man. Instead, one decision leads to another, and here he is.

I wonder about his mother. Does she care where he is? Does she know he sleeps on the streets and hustles for heroin and gets beaten regularly? I conjure a vision of a mother sitting in a living room somewhere, gazing out from a window, sickened to her core that her little boy went from middle school beer tasting to high school vodka to pot to acid to cocaine to riding this wild horse.

He knew I wanted to photograph him. And he was quite happy with his reflection as he looked at it, as well as he could understand it in that state.

As I write this, I am sitting in my cozy little house sipping a glass of Pinot Gris and wearing a warm cinched corduroy jacket with turquoise leather inlay cowboy boots. I think about him often.

I wonder if Al Pacino returned his hello.

Cheryl Strayed: An Unaltered Image

I can sense that her image is important to her, and that this photo session will not be one where she is not invested in its outcome. It is not her ego that is driving her, it is her anticipation. She knows what is about to happen in her life, how her world will change in a few short months, and there is a hint of desperation in her stance.

Success can be overwhelming, and for someone like Cheryl Strayed who works from her intuition outward, she is trying to brace for the wave that will certainly alter the course of her family.

This was my second time photographing her. The first occasion was when we made her author photograph for her newly released book, Wild. I had met her years before at a party on my street, and as I frequently do when I see someone I would like to photograph, I approached her and asked if I could do so. I never question why I want to photograph someone, i just go for it.

It took a few years before we finally got into the studio, coinciding with the time that she needed her author photo. She was not the easiest person to photograph, as she was difficult to “reveal”…..she held back from letting herself become free before the lens. However, I could see a heat, an intensity that ran so deep, and I took the time to find a way in. I was surprised, because Cheryl is known for her openness and exposure of self in her writing. But the camera can conjure up a whole set of feelings as we place ourselves center stage before the world. I understood this. I found this aspect of her to be utterly endearing, and a purposeful platform from which she could rely upon as she embarks on the notoriety that this book will surely bring to her. A bit of self consciousness and doubt are good antidotes for anyone who is a rising star.

As we got to know each other, she quickly let down her guard, especially when I asked her to scream foul expletives into the air. We collapsed in heaps of laughter as she spewed out word by word, randomly surfacing the most blatant in her mind. Click. I knew which image would make it to the top three, and I was not surprised when she selected it as her favorite for the book jacket. Exuding just the right tinge of sexuality with a splash of backcountry confidence, there she was in front of me: lovely, poised, certain and wild. I saw the stray hairs that flew about, but I restrained from moving them. This was her, in all of her provocativeness. Let it be. Why alter that reality?

Now I was here to photograph her for the magazine, Poets and Writers. The specs were well defined, from typeset placement to locations to editorial vs portrait styling. I had a grand time with Cheryl in her home, poking into hallways and bedrooms and recessed living areas. My daughter was my assistant on this day, and we both marveled at how she can ignite a conversation with a deliberate focus of her yearning blue eyes, a tilt of her head and a deeply penetrating question.

When it was time to upload images to the magazine, once again, I was faced with a choice regarding how I would edit the images, as I retain rights to make those decisions. There was one photo in particular that was bothersome. During the shoot, I had failed to see a strand of blond hair that was twisted into a pattern that detracted from Cheryl’s face. It looked like a starburst, shot close enough to the camera that made what is referred to as a “hot spot” on the image. Glaringly white, it drew the eye downward toward its center. I agonized over this part of the image, kicking myself for not seeing it so I could have moved it into place where it would not have competed with her facial expression.

As I started to alter it in Photoshop, once again, I halted myself. This is who she is. Just because this is a rising star, photographed for a highly regarded magazine, why should I now foray into something I have long kept at bay in my work: the degradation of an authentic image just for the sake of so called beauty?

I decided to leave the starburst piece of hair intact as a testament to the miracle of photography. At times we capture something we never see while photographing the subject. This is the true delight of making images, when we, the photographers, are startled by something we did not know was present.

This starburst was something I could not have created myself. The more I looked at it, the more I saw how it was a symbol of the truth in Cheryl: although a rising star, the showmanship brilliance rests more upon her shoulders than in her soul. One can see quite quickly that Cheryl Strayed is all about the journey and not the destination.

Her star is shining now, with book tours and interviews and even discussions of larger events that will rock her world. But deep within her soul is where her truth rests, not within her stardom. If one looks past the dazzle of stardom and the bursting success that is now surrounding her, you can reach her soul through one look into her intentional eyes.

Imperfection is, after all, the gateway to sincerity.

The Truth Of A Still Image

For many years, I have brought this question up during the classes I teach, delighting in the hearing the discussion that would follow. A still photograph is, after all, a replication of a slice of time, right? But yet, a still image also takes on meaning from the perspective by which it is viewed. Connotations derived from our own experiences “color” the image, and attaches attributes to the photo. And in this digital age, where post processing can greatly alter an image from its original state without notification to the viewer, how can we ever trust that a photograph truly reflects reality?

The moment I enter a scene and select a subject, the decision making begins. How I angle the camera, which background I choose, how I like to see the light fall on the person’s face are all elements that can greatly affect the mood of the image. I know when a photograph might evoke emotion and when it might have less appeal to a viewer, and I deliberately discern how I want to construct that image.

People frequently tell me that my photographic style celebrates the integrity of the subject and preserves authenticity. While I certainly strive for more of a connection between me and the subject rather than the camera and the subject, I still believe that a photograph never tells the full story and by the time an image is made into a print, so many decisions were made that the viewer is only seeing one fraction of reality, and this is from the photographer’s and viewer’s standpoints, not from the subject’s.

I have a trick I use that works like a charm every time I want to shift the power from camera operator to the subject. I wait patiently for this to occur before I press the shutter release, resulting in what many refer to as “capturing the soul of the person”. This look in their eyes has nothing to do with photography, and everything to do with humanity and our interplay as human beings relating to each other, regardless and usually despite of the overlay of language. However, even with this practiced altruism, I still walk away feeling like there is so much more I could portray about the person I am photographing. I never feel satisfied that I have “captured” someone. Never.

I leave every single encounter with a longing. A heart wrenching longing that is insatiable and tormenting. I leave something behind, many things, when I photograph someone. Like a lover left on the shores of a far away country, these people I have photographed play out their stories in my head, one by one, over and over, begging to not be misunderstood.