In Western developed culture, we rarely spend time feeling each other. Fleeting eye contact, minimal touching, hasty interactions, we don’t often permit enough time with each other. We seek what we need and want, and move quickly into our next desire, rarely lingering long enough to foster communication that goes deeper than what is easily defined by words. Lovers might feel this type of encounter, but how often do we allow ourselves to feel this with someone who is not our most intimate partner?

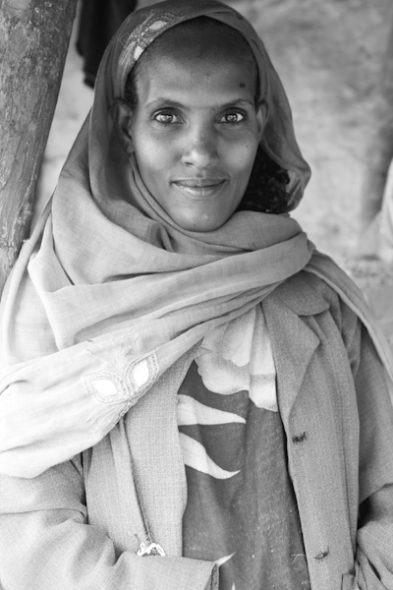

Here in Ethiopia, there is a purity of spirit that reaches out and envelopes even the most calloused person, should they dare to shed the shackles of puritan posturing and let themselves truly feel the deep presence of another human being.

Mankind started here in Ethiopia; we all come from this place. In new age terms: we are one on this Earth. When Western lifestyle is shed and an openness to Ethiopian spirit is permitted, you can fall in love with those you meet here.

If I bring my camera into operation too soon, before I feel silent heart exchange, I cannot record the love that is expressed through the beautiful and powerful retina of our eyes. But if I engage with someone and I am open to this manner of human encounter, at times the camera looses its intrusive power and love can be viewed via the image. I treasure these precious images, each and every one, and count on them to remind me how capable we are as human beings to express love to one another.

Back home in my daily routine and distractions, I look into the eyes of these people and know that an area of the world exists where love and tender care comes first, all else is secondary…or even deemed useless to many. Often, I have seen many Ethiopians tilt their heads in endearment toward me, their eyes expressing that they know how lonely I must feel at times in my culture based upon independence.

Inevitably during these exchanges, tears well up and flow out of me, from inner recesses I rarely pull from in my comfortable life. I turn away, as it is extremely upsetting if Ethiopians feel that they have disturbed another human being. But I feel each tear, letting it absorb back into my skin as a medicinal antidote for carrying me forward.

And I believe, with all of me, that this is how we were born to love each another.