Kuye is one of very few girls who get to attend high school in this southern area of Ethiopia. This is not due to a lack of desire, they simply have too many duties to perform at home and the costs to attend school are outside of most families’ reach. Within Kuye’s class, there are 42 students and only four of them are girls. (Hear students at Konso High School)

Kuye’s mother, Taiko, notices other girls at the market who are educated and wants the same for her daughter.

Taiko was able to obtain a scholarship and academic support via a program developed by Mercy Corps. Kuye is flying down the path toward her education goals. Her favorite subject is social science, which includes computer programming, and she wants to become an engineer. She has seen women in other countries work in this field, and she believes it is time for Ethiopia to have more female engineers.

Kuye knows that she is a pioneer of sorts. There are people in her village who still think a girl “is not a good girl if she goes outside of her house” to do things outside of her traditional activities. To some, this might seem patriarchal and dismissive of women. But it is more complex than this simple conclusion. Girls are highly regarded in Ethiopia and they are cherished to the point of believing they will (and knowing they can) be stolen, and therefore they are highly protected.

Most women who are not educated end up living a life full of extreme physical burden. They fetch water and firewood, carrying bundles of heavy loads for miles, sometimes days, to help provide for their family. They suffer during child birth, often losing their baby and living with resulting injuries obtained during days of laboring. Life indeed can be hard in the rural areas of Ethiopia, for both men and women.

Kuye wants to alter this path, and show the world how capable a woman in Ethiopia can be. I give her my camera, and she quickly learns how to operate it, snapping a photo of her mama Taiko and gleefully turning to all of us with excitement about the beautiful image she just captured.

She is a quick study, smart as a tack.

Her hope for her future is to “finish school, get a good test result and go to university, then return” to help her village. I can only imagine what she would do if she attains this goal.

She cites gender inequality as being an issue in Ethiopia, but she has a simple reason for its existence. She points to the fact that boys, at an early age, begin to carry heavier loads than she can carry. They appear stronger and and more powerful, just because they can pick up heavier objects. Kuye believes that gender equality begins at home, with each parent treating boys and girls equally, and instilling within a young boy’s mind that his sister is as strong as he is.

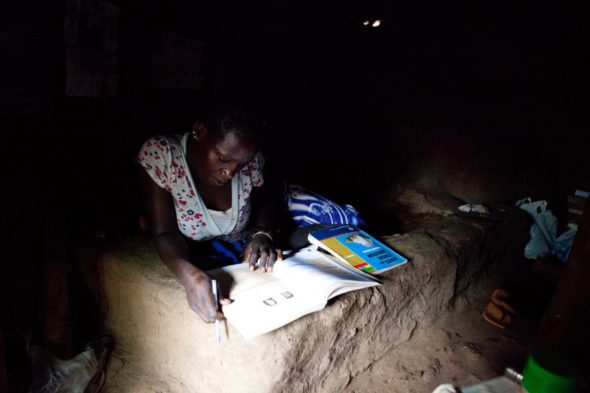

I ask her where she studies when she is home, and she shows me her bed made of mud and clay. To the left of the bed is a small shelf made from hay and mud and I notice again the coconut oil. This is a prized possession, as it makes her feel beautiful and a part of the group of students in her class. Like any 18 year old student, she wants to fit in.

And she wants to feel like a girl, all pretty and smelling wonderful as she faces her new world and emerges as a strong and educated woman.

I will cheer her on. all the way through her university years.

One coconut oil jar at a time.

(Photo of Taiko above by Kuye Orkaydo)

(All images for Mercy Corps)